Startup Equity Explained: SAFEs & Convertible Notes

An Appendix to The Startup Equity Explained Series

In Part One, we discussed some of the early considerations around allocating equity to co-founders, early employees, advisors and professional service firms. We quickly touched on how ownership stake gets diluted each time a new shareholder becomes involved. Part Two will cover is Venture Capital Portfolio construction, Liquidation Preferences, Broken Cap Tables, Valuation & Dilution Ranges and Down Rounds.

Before getting into all of that, by request, here is a quick overview on SAFEs and Convertible Notes that are mentioned in Parts One and Two:

SAFEs and Convertible Notes.

Before getting to a priced round, Founders might need to raise initial funding to demonstrate enough traction to an investor. They do this with these two types of instruments:

A SAFE stands for Simple Agreement For Equity, you might also come across a Keep It Simple Security (KISS), which is similar enough to a SAFE that this information can apply to both. Contrary to popular belief, a SAFE is not actually a debt instrument. The advantage of this for Founders is that it means there is no maturity date (when the funds need to be paid back) or accrued interest to worry about. An additional advantage of a SAFE is that the legal paperwork is generally much less compared to a convertible note or a priced financing round (as the name implies, it’s meant to be simple). The consistent mechanism of a SAFE is that an investor gives a certain amount of money to a founder, without explicitly placing a certain value on the equity of the entire company. This differs from a priced round, where all equity holders know the value of their holdings at closure. If the investor offers a post-money SAFE, they set a fixed ownership for themselves whereas a pre-money SAFE is only determined after the priced round. Once the SAFE is signed and the funds are wired, the holding value of the investor’s investment sits in purgatory, up until the moment the company has a priced round. This is when their investment will convert into Preferred Shares at a price determined by a combination of the valuation set by the later investor and certain provisions embedded within the SAFE contract.

Simple Examples of a Pre-Money & Post-Money SAFEs:

Investor A and Startup A agree on a SAFE note, where the investor gives Startup A $1M.

One year later, the company raises a priced seed round at a pre-money valuation of $7M. The new investor contributes $2M. If there was no SAFE, once the round closes, the company will have an equity value of $9M (Pre-money valuation + funds raised). The new investor is paying $2M to own 22.22% of the company ($2M/$9M). Seems simple and easy enough. Once SAFEs and earlier investors get involved, this is where the complexity ensues.

With the presence of the SAFE, it would be as if the early investor was participating in the round (even if they gave the funds a year earlier). The new Post-Money valuation of the company would be $10M ($7M pre-money + $3M funds raised). The SAFE investment amount of $1M would represent 10% of the equity value, once the round closes, and the new investor would own 20% ($2M/10M). This would be an example of a Pre-Money SAFE, without any valuation cap or discount (more on this shortly). In such a case, the SAFE investor has no way of knowing what their investment will be worth, until the priced round closes. SAFE investors will often want some idea of what their investment will be worth, not to mention additional provisions to compensate them for providing the funding when the company had less proven traction.

As such, SAFEs will generally include some combination of the following terms:

Valuation Cap: Regardless of what the pre-money valuation of the priced round is, the SAFE investor might want to guarantee themselves a minimum amount of ownership after the round closes. They can control this by ensuring that the amount of shares they will be getting will be calculated on the pre-specified max pre-money valuation, the Valuation Cap, instead of the actual pre-money valuation of the round. Effectively, in the case where the new investor prices the round above the valuation cap, the SAFE investor will get to pay a lower price for their equity. The standard used to be around $5-10M before a priced round, but now could range anywhere from $2-20M depending on market conditions, stage of the business and other factors.

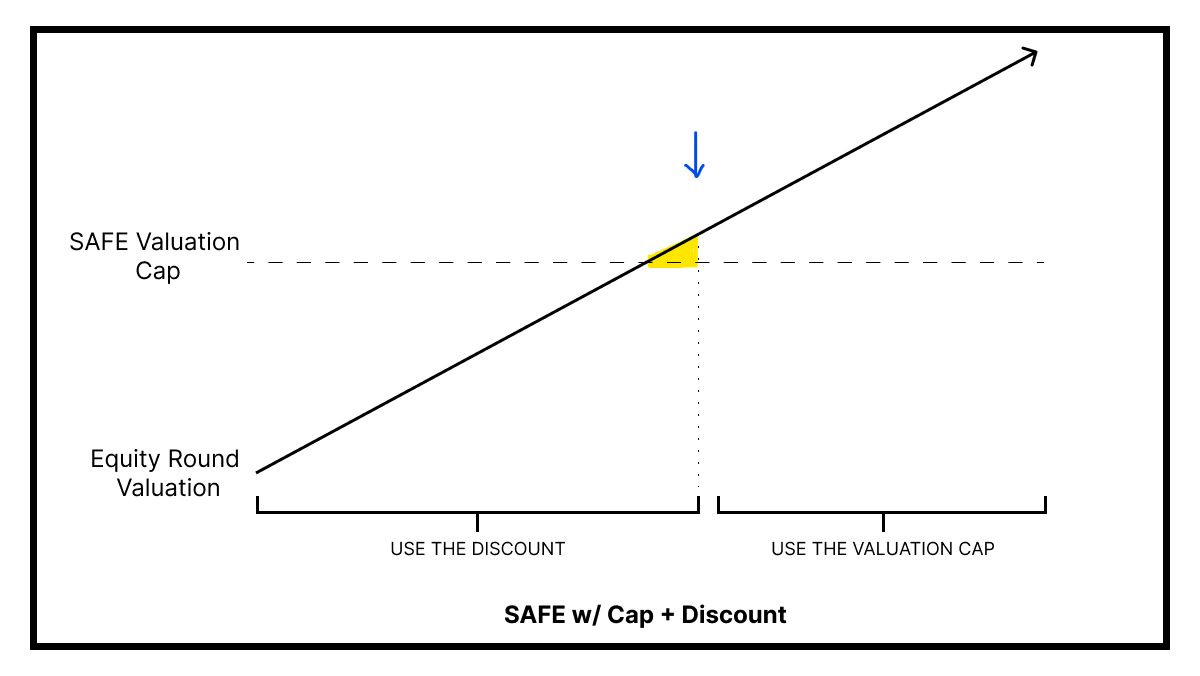

Discount: Similar to the Valuation Cap, the SAFE investor wants to pay a lower price compared to the newer investor, therefore they will pay a predetermined discount to the round. A typical Discount rate will be between 10-25%. The Discount is better for the SAFE investor at low valuations but worse the higher the valuation climbs. If the SAFE investor were given a choice between a $10M valuation cap or a 10% discount to the round, the indifference point between the two options would be at $11.1M ($10M/0.1). Normally the SAFE holder will get a Valuation Cap or a Discount but will sometimes get both (depending on market conditions and how competitive the round is).

Pro rata rights: This is normally standard even with priced rounds but SAFE holders will want the opportunity to maintain their ownership percentage as future financing rounds occur. In order to maintain their ownership, they would have to continue to invest more in future rounds. This is a pretty standard feature, therefore be careful who you raise money from, since they will have the right to maintain their ownership far into the future.

If the SAFE was post-money, let’s say $2M on a $10M Valuation cap, the investor knows they will own at least 20% of the company following the completion of the priced round. If the priced round is below the valuation cap, the SAFE investor will get to benefit from the lower price and end up with greater than 20%.

It can also happen that an investor will want a Valuation Cap and a Discount. If it’s a Post-Money Safe, it guarantees them a floor and ceiling on their ownership. This is obviously much more beneficial for the Investor, which is why generally as a Founder you should insist on them only getting one of the two. From the perspective of a Founder, you are better off if they have a Discount, since if you raise a bigger round, the SAFE holder will end up owning much less of the company compared to if they had a Cap.

(Source of Chart Chris Harvey. See Linkedin Post)

To further complicate things, sometimes your first SAFE might not be sufficient, so you may need to raise another SAFE or even a convertible note as a bridge until your priced round. This is where conflicts can emerge between the prior and the new SAFE investors (if they are not the same party). To prevent this from happening, the first SAFE investor can have provisions to ensure their initial investment can benefit from the new terms and conditions from the second safe, assuming they are more desirable for the investor. While SAFEs are a helpful tool, especially at the earliest stages of a startup, a common problem that can occur is that these SAFEs or convertible notes can contain provisions that are too preferable for the early investors, that can scare off later investors at the Seed or Series A. This is why it is important if you raise a SAFE, to make sure that the valuation cap is not too low, the discount is reasonable, and that there are not any harmful stipulations. Even beyond these terms, it is important not to give up too much ownership and suffer excessive dilution very early on. This is a dynamic we will elaborate on during Part Two, but a common theme for all equity holders to acknowledge is that upstream funding and dilution decisions will compound each round.

While SAFEs are a standard way to raise money when parties cannot come to an agreement on equity valuation, the other alternative is to opt for a Convertible Note. As the fundraising market has gotten more difficult, companies increasingly have been opting for Convertible Notes. Convertible Notes can have a much wider range of provisions attached, which I will not cover but unlike SAFEs, they are debt instruments, which means they will need to be paid back, unless they convert. The standard length is usually 18-36 months, but can extend longer. This is why it makes more sense for companies that have already had a priced equity round and are at least generating revenue. These notes will generally also contain accrued interest along with much more stringent terms and conditions not present in a SAFE.

SAFEs are generally used before there is a priced round, whereas Convertible Notes can be used at any time but usually later in a company's life. A primary reason companies opts for a Convertible Note is to serve as a Bridge Loan until they expect to be able to raise another priced round, or have a liquidity event. This becomes necessary when they find themselves in a liquidity crunch but lack the traction needed to be able to raise another priced round at an adequate valuation. Just because a company chooses to raise a Convertible Note does not necessarily mean things are not going well with the company (more on this in Part Two), however the attached provisions on the Note are intended to benefit the Investor. This is why when capital markets start to tighten, Convertible Notes become much more prevalent.

While a company will typically ask their existing investors first, almost as an advance on their next round, sometimes companies will raise these Notes from new parties. A prominent example of this was Airbnb raising $1B from Silver Lake and Sixth Street Partners at the onset of the Global Pandemic. This ended up being an excellent move for the investors, who got warrants at a valuation of $18B, when the company was last valued at $26B, and would IPO less than a year later at market cap above $100B. While the Airbnb example was extreme because of the pandemic, it is not uncommon for Convertible Notes to contain all kinds of discounts, valuation caps, repayment schedules or covenants (rules) that are far more complex compared to a traditional SAFE.

At least one common feature of a Convertible Note, that is less common in SAFEs, is that they will stipulate a minimum valuation and amount raised for the priced round in order for their note to convert. This protects the Convertible Note investor but could come at the expense of all the other equity holders, if the company cannot successfully raise. Since Debt instruments will have priority over equity, the Convertible Note investor will need to be repaid first. Despite the potential ramifications, the Convertible Notes can be an important tool to ensure the long term viability of the company or avoiding down rounds (To be explained in Part Two). However, you generally want to make it as easy as possible for future later stage investors. Even with lenient terms, SAFEs and Convertible Notes can add complexity, therefore the best solution is to try to avoid Bridge Rounds altogether.