Avoid Ruin with The Precautionary Principle: An Introduction To Nassim Taleb

Rule # 1: Don't Blow Up Rule. # 2: Don't Blow Up.

If you are unfamiliar with Nassim Taleb, the author & Twitter provocateur, you have surely encountered some of terms and concepts he created or popularized. His Incerto series includes popular titles such as The Black Swan and Antifragile which were greeted with fanfare upon their release and continue to live on recommended book lists from investors, founders and rent seekers alike.

Between the publications of Antifragile (2012) and Skin in The Game (2017), Taleb co-authored a paper, “The Precautionary Principle (with Application to GMOs)” (2014) which generated a considerable amount of controversy upon it’s release. The scientific community were aghast because the Taleb and his co-authors had concerns with genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Being publicly against GMOs then and still today is the easiest way to get looped in with Conspiracy Theorists, Pseudoscientific Fitness Influencers or Hysterical Hypochondriacs (this group also represents my key Subscriber base).

Jokes aside, regardless of your views on GMOs, Taleb’s discussion of the Precautionary Principle is worth re-examining, as it’s helpful to understand the different types of risks, and why most risk models fail. At the same time, let’s take this time to re-visit some of Taleb’s key ideas when it comes to risk.

Keep reading to find out why you should use the Precautionary Principle to ensure your own survival.

But first, make sure to hit the Subscribe button below to be one of the 1,000 Subscribers to Serviceable Insights to get articles like these, delivered directly to your inbox.

If this week’s article does not interest you, please check out some other recent ones:

Principle Origins & The Philosophy of Nassim Taleb

“When a proposed action carries even a small chance of bringing irreversible, system-wide ruin, we should err on the side of caution—and the burden of proving it is safe rests with the proponent, not the critic.”

“The Precautionary Principle” originated in the 1970s in Europe. First appearing in German environmental law, showing a shift in how regulators wanting to acting on risk instead of waiting for harm. This perspective gained momentum in the proceeding decades and has extended to other sectors. Yet when it comes to managing risk, there’s the academic view and the practitioners perspective.

Nobody understands the practitioners perspective better than Nassim Taleb. He’s been successful in finance and as an author because of his reflections on risk; he credits his experience as a trader since traders and hedge funds’ livelihoods are tied to their ability to manage risk. If they can’t manage their risk properly, they blow up, creating a natural evolutionary cycle. Academics on the other hand, can be wrong for decades without consequence since they are tenured salaried employees at publicly subsidized institutions. This is why when it comes to risk, Taleb suggests learning from people exposed to the impact of bad decisions; people with skin in the game.

Black & Gray Swans

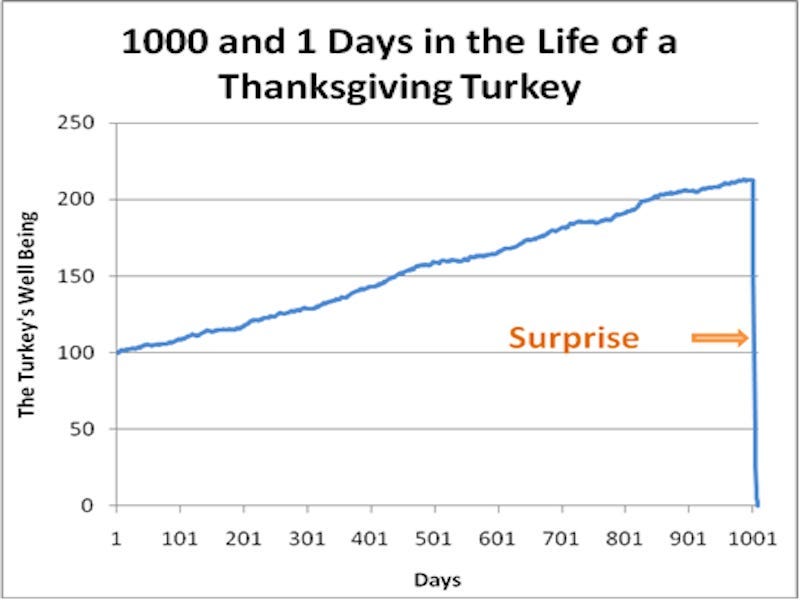

Wall Street traders equipped with sophisticated academic models blow up by understating rare but extreme outcomes. In the stock market, most days are characterized by small gains or losses, which in aggregate trend up over time. From the perspective of an investor, this seems great. Investors portfolios are worth a bit more each year on paper and investment professionals get to charge fees based on these higher asset values. Individual stocks might rise or fall dramatically but market wide, volatility remains low and everybody is happy. However, this can create a false sense of safety. Taleb often gives the turkey example: A turkey is fed every day for 1,000 days, growing ever more certain the farmer cares for it—until day 1,001, when it’s killed for Thanksgiving.

Since the overwhelming majority of trading days are low volatility, when you plug market data into a risk model, it makes extreme high volatility days seem so unlikely, it’s as if they aren’t there. However, they do eventually happen and can wipe out years or decades worth of gains overnight, suddenly popping the illusion of safety. Just like the turkey on Thanksgiving. Each time this happens, investment professionals will say it was unforeseeable, unimaginable but most importantly: not their fault.

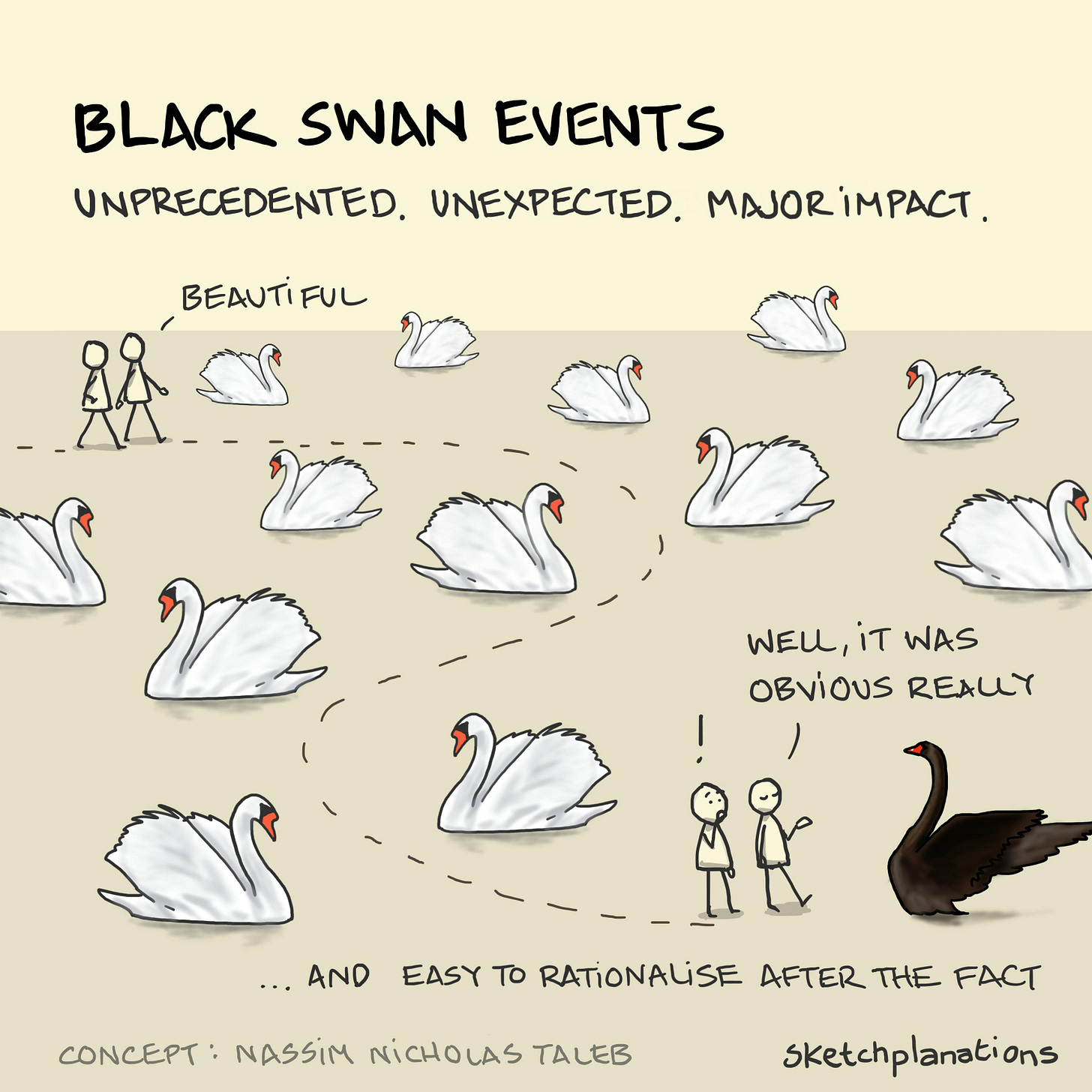

They will call it a Black Swan event. However, by saying that, they will only prove they don’t know what it is. A real Black Swan event would be an extreme event, falling outside any believed range of outcomes. Think Aliens arriving on earth or a horse winning a professional golf tournament. Neither a market collapse nor a pandemic qualify. Historically, the US enters a recession territory every decade with market sell offs happening more frequently. Major, deadly pandemics are known risks that happen infrequently. Most of us are just too young to remember the bubonic plague or the Spanish flu. These extremely rare but known risks are Gray Swans.

Understanding the difference between unprecedented and very rare events is an important step for risk management. Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld popularized the notion of different forms of military intelligence into:

Known-Knowns: Risks you are aware of and have insight into

Known-Unknowns: Risks you are aware of but lack knowledge or verifiable data

Unknown-Unknowns: Risks you don’t even know exist

This is important for military planning but apply to any type of risk activity. On Rumsfeld’s matrix, Black Swans are generally Unknown-Unknowns. Most military commanders or hedge fund traders, have an idea how to handle the first two types of risks, but it’s in the third type, which are the most consequential, that often carry the greatest potential for danger.

Ruin Dynamics and Systemic vs Self-Contained Risk

If somebody handed you a glass of water and said there was 4% chance of dying immediately, would you drink it? What if they instead said the entire planet would explode. Would that change your decision making process? Should we as a society treat these type of scenarios differently?

Nassim Taleb believes we should. Risks that only impact the principal actor or small amounts of people, should not be treated the same as events carrying systemic wide risk. If the ultimate goal is to ensure the continuation of the human race, we should do our best to eliminate or minimize risks that put this in jeopardy.

When negative risks are contained only to the person performing the action or a small number of people, these are considered localized harms. An example of this is driving. More than one million people die in car crashes each year, but it’s impossible for one single driving accident to kill more than a handful of people at a time. A fender-bender in Athens can’t physically harm somebody in London. Therefore Brits shouldn’t have a say in banning driving in Greece. When harms are localized, each person can take risk decisions on their own behalf. This is why despite the high death counts, banning driving isn’t necessary. Requiring insurance serves as an adequate system since repeat offenders would eventually be uninsurable.

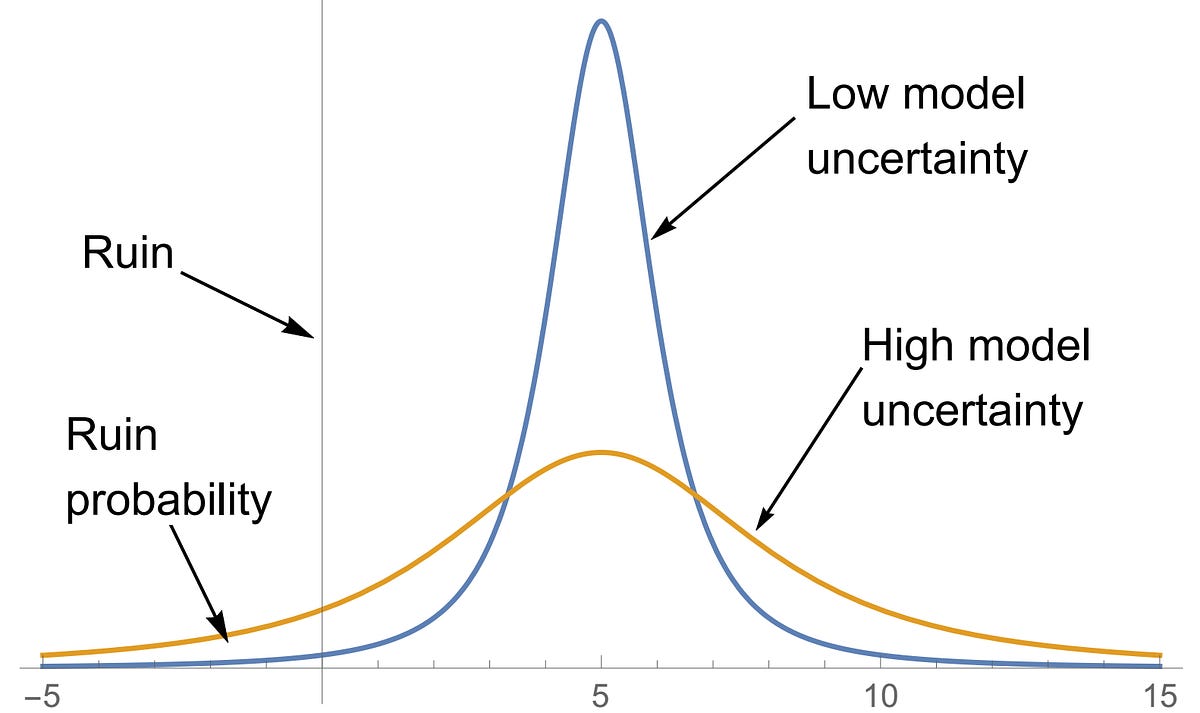

However, some events have the potential to cause irreversible catastrophic damage. This is ruin risk. In these cases, more stakeholders should weigh in. Especially when all it takes is a single single instance (Ex: A major flood, pandemic or nuclear explosion) . This is why an individual shouldn’t have the right to risk blowing up the planet to quench their thirst. One problem with the scenario I provided, was it presented the question as if the probability was known to be 4%. It’s one thing to make decisions when the probability is well understood and a completely different thing when the model has little to no predictability. This goes back to the Known-Knowns versus Unknown-Unknowns.

When there is low confidence in the model and the potential for ruin, more prudence is needed. Dealing with Known-Unknowns or Unknown-Unknown risks, means the probability for ruin could be uncomfortably high. This is why more diligence should be done to improve confidence in the model before introducing this risk. Especially when some effects are irreversible.

“If the risk is one of ruin, standard statistical inference breaks down; absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” Taleb et al, 2014

The Ramifications & Conclusion

Taleb argues the conventional approach of putting the burden of proof on regulators or consumers to prove the danger before introducing these risks is backward. Anyone looking to introduce these type of risks should first prove there’s near zero probability of ruin first.

This is why he’s against GMOs, engineered pathogens or gain-of-function virology. These new and largely untested methods, have a lot of uncertainty coupled with the potential for ruin. Naturally, this drew the ire and criticism from the science community; taking his argument as being anti progress/science. Others say dismissing things with minimal risk of ruin but with guaranteed advancements for society is foolish. There was a lot of criticism to the article and concept at large.

Taleb failed to convince anyone to remove GMOs from the food system, and lost some clout with the science community. However, this line of thinking alerted him early to the potential risk caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020. He was among a group that warned the White House of the risks of the pandemic. They advised to close their borders to prevent the spread, implement aggressive testing, lock-downs and protecting the elderly before the pandemic could reach the US.

The White House, and pretty much every other country did not take their advice. Instead of acting quickly and decisively, they opted for a wait and see approach, to not unnecessarily cause economic harm. Well we know how things played out.

While this might not have changed anything, Taleb’s perspective on risk, could have potentially reduced the spread of the pandemic. This is because he understood the difference between localized and system risk, ruinous events and how to manage risks when the probability is not well known. Insurance, elimination or avoidance. You don’t need to be a best selling author or accomplished trader to understand the key concept: Make sure you don’t blow up!

Thank you for reading. If you liked this article please Subscribe below. I publish articles on a wide range of topics from business, books, current events or anything on my mind.

"A turkey is fed every day for 1,000 days, growing ever more certain the farmer cares for it—until day 1,001, when it’s killed for Thanksgiving."

Perfect example of a turkey-like investment: catastrophe bonds. https://youtube.com/shorts/S006Pz0BbJ0

Cat bonds pay interest if nothing happens, but the principal can be 100% wiped out if a natural disaster happens.

It's insane that anyone would buy this stuff.