How to (Actually) Think Clearly

A summary to Clear Thinking from Shane Parrish Part I

My company started a book club, now I know what you are thinking. Book clubs are a waste of time.

They are often an excuse for self-proclaimed intellectuals to convey status. A venue where they can embarrass so-called friends and acquaintances with their superior insights. Others might just be there for the snacks or excuse to socialize without having read the assigned book.

I have been part of several of such groups; good times were had and most ended without violence or death. This is why when my company was brainstorming ways to get employees engaged with the new core operating principles we were rolling out, I suggested we start a book club.

As the principle for the month of August was to "Be fact-driven and purposeful.” the first person that came to mind was Shane Parrish. Parrish worked in a Canadian intelligence agency before founding the popular website Farnham Street. Farnham Street is dedicated helping people “Think better. Make smarter. progress in () life and career. Find your focus.” Between Farnham Street, his newsletter Brain Food and his YouTube channel, Parrish has an audience of millions, including yours truly.

This is why for the inaugural book club meeting, I suggested Shane’s book, Clear Thinking. If you are serious about making better decisions and putting yourself in the best position to achieve your goals, Clear Thinking is a must read. In today’s article I give an overview of some of the principles and ideas from the first part of the book, with the hope this inspires you to read this for your own.

Check here for Part II.

Continue reading if you want to learn how to think clearly!

But first, make sure to hit the Subscribe button to join 1,000+ other Subscribers that get Serviceable Insights delivered directly to their inbox each week.

If this week’s article does not interest you, please check out some other recent ones:

Section One: Enemies of Clear Thinking

1.1 Think Badly or not at all?

Intelligent people regularly do stupid things. A stupid action isn’t when you get an undesirable result, but from following a process that obviously wasn’t going to work. Stupid actions usually arise not because we lack intelligence but because we weren’t thinking clearly.

Think back to the last time you did something you immediately regretted. Did you spend minutes to hours on the decision or did you just react?

Rationality is wasted if you don’t use it. Too often logic gets crowded out by other factors: our default actions or behaviors. Sometimes we are quick to anger or fast to assume intent. When we rely on our defaults, instead of our rational thought, we are more likely to do stupid things, or actions we will later regret.

Being aware of these barriers to clear thinking is the first step to try to prevent them from crowding out rational thought. Think of these barriers as little Gríma Wormtongues from Lord of the Rings whispering into Théoden King of Rohan’s ear. Only once they removed Gríma from his side could he think clearly again.

Here are some of the barriers to clear thinking:

1.2 The Emotion Default

Parrish uses the example of Michael & Sonny Corleone. One doesn’t allow emotions to cloud their judgement, the other succumbs to them. Predictably one dies much sooner than the other. Sonny’s inability to manage his emotions while making decisions causes him to make many unforced errors. This reckless behavior creates a huge mess for the Corleone family, forcing Michael to clean up the mess.

There is a Sonny Corleone in all of us.

When we are reacting out of anger, sadness or another emotion, we aren’t in an optimal headspace for decision making. Whether this is how we comport ourselves in our personal lives or make big decision for our careers, our emotions at the time of the decision should not be the loudest voice.

(Not a fan of The Godfather? you can also check out Stoicism Explained by Star Wars)

1.3 The Ego Default

What matters more, appearing successful or being successful?

The answer might seem obvious but hubris has been the ruin of many. Not only is it enough to win, people want the praise and trappings that come with it. Before long, people get more satisfaction from the latter, than the former and that’s when trouble arises. This is why victorious Roman generals would have a slave (servus publicus) stand in the chariot with them whispering reminders their mortality (“Memento mori”).

It’s also true that without confidence, you won’t accomplish much. What’s important is that your confidence needs to come from competence or it’s simply hubris. Being aware of your abilities and limitations is important when making decisions. Overestimating your talents or worth can get you into dicey situations.

It might seem obvious but this happens all the time. There’s a reason why one of my most viewed articles to date is titled “Should I Go into Debt for a Rolex”. People want to hack their way to status, which they wouldn’t need to do, if they had it.

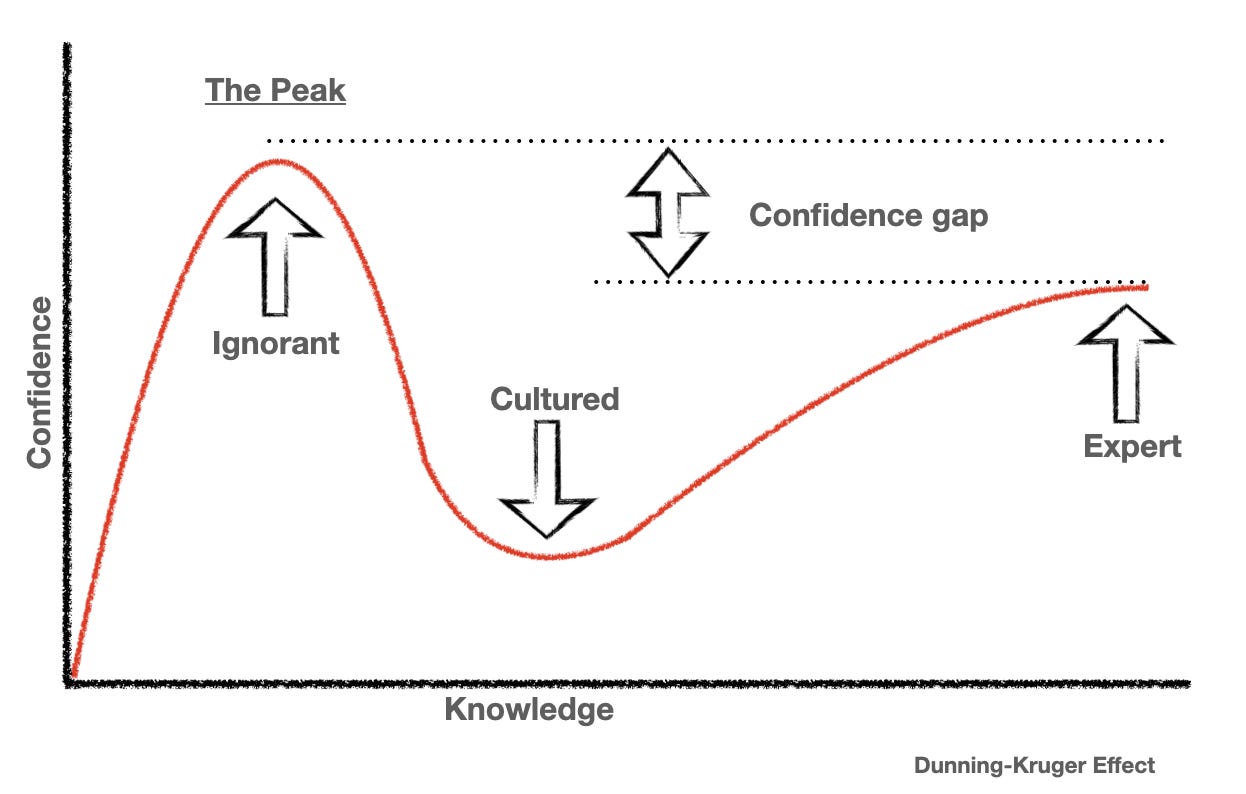

Parrish reminds readers of the Dunning-Kruger effect; a little knowledge can give you unjustified confidence which begins to decline as you get a bit more.

1.4 The Social Default

How often are our choices our own? Are we doing things because we believe they are right or because that’s what everyone else is doing. Have you ever started clapping because other people around are? Sure you have. It’s hard to fight the urge. Social pressure is a powerful thing.

It’s not fun to feel part of the “outsider group” we want to be accepted. We don’t want to stand out, so we would rather do the same as others even if we don’t agree. We are effectively outsourcing our thoughts to others. Sometimes there’s strength in numbers and you can benefit from the wisdom of the crowd, other times that wisdom is madness.

As we increasingly outsource our thinking to LLMs or our investment decisions to ETFs, we are not really thinking, we are operating on auto-pilot and letting the universe decide our fate. If you’re an economist that believes that humans are rational decision makers, perhaps this is a good thing. For those of us living in the real world, we are just as likely to be listening to people that have also yet to abandon their defaults. Which is why groups can hold wrong views for a long time.

Parrish gives the examples of virtue signaling. Many people suddenly adopt the same set of professed beliefs because it costs them nothing to be wrong since they are sticking with the herd. He uses the example of a Princeton Professor that asked his students what their position on slavery would have been if they were white living in the south prior to abolition. Guess what? Everyone in the class believed they would have been abolitionists, that would have spoken out against slavery and worked tirelessly against it. That’s easy to say in 2025 but we know people rarely want to go against common convention.

Even if they felt like it was wrong, they probably wouldn’t have spoken out against it. They wouldn’t want to have risked the backlash by straying from the consensus. How often do you see somebody decidedly right-wing or left-wing politically speak out against their parties orthodoxy?

Ironically it’s those that go against convectional beliefs that often make history. We only know or care about artists who dared challenge convention or take risks. You might underperform but you also might change things for the better. This is also why best practices aren’t always the best. By definition they are average (I wrote about this in Benchmarking is Lazy).

Contrary to what people think, being right or wrong isn’t based on if people agree with you or not. You will be correct if your facts and reasoning are correct. Unfortunately in a corporate environment, risk taking or trying things outside convention is often discouraged. Managers or execs would rather stick with the crowd so if things don’t go their way, they can minimize their own involvement in the outcome. Buffett talks about the agency-principal problem. Personal gain/loss ratio is too obvious, most people just don’t want get fired so trying something new and risky isn’t worth it. If it works out the company benefits more than they do, if it doesn’t work out, they get fired but the company persists.

1.5 The Inertia Default

The reluctance to act or change is very powerful.

How often do you change toothpaste brands? Experiment with new hairstyles or take a different route to work? One of my favorite tv shows Westworld shows humanoid robots following different loops, yet upon reflection, we humans follow very similar loops since we rarely stray from pre-determined behaviors. We stick to decisions we made long ago, regardless of how our environment has changed or what new information has come to light. How open minded can we be if we don’t change?

Shane shared an experience many investors can relate to. He invested in a promising restaurant chain with a CEO, Shane highly trusted. In the years following the investment, the CEO made many small transgressions which were easy to rationalize at the time. Eventually the CEO’s attitude impaired the investment. Only when Shane zoomed out, did he realize the signs were there but he was too slow to change his mind. If he were quicker to react, he might have been able to salvage his investment.

Objects never change if left alone. They don’t start moving on their own if not touched. Once minds are set in a direction they will continue in that direction until an outside force forces a reconsideration of that view. This is why it’s not a coincidence conspiracy theorists often live alone in a cabin in the woods. There’s nobody to talk sense to them. This further gets into problems with LLMs re-enforcing problematic beliefs or when people create echo chambers by not seeking out contrary viewpoints or ideas.

There are many reasons why people don’t want to change. Anybody working in sales & marketing pros understand this well; since their job is generally trying to convince somebody to change or adopt a new behavior. People are afraid the change will lead to worse results. People will prefer discomfort over uncertainty. Assuming you clear the uncertainty hurdle, you next must contend with another: the resistance to new effort. Especially if they aren’t convinced this new effort won’t lead to a worse outcome.

Good salespeople or marketers can give their target audience the confidence that adopting their product/service will not require a lot of new effort and will lead to a better outcome. You need to be the best sales person for clear thinking.

How often do you double down when you are wrong instead of stepping back, re-evaluating and admitting you stuck with the wrong choice for too long? Don’t let your reluctance to change prevent you from making a better decision.

1.6 Default to Clarity

We can’t eliminate our defaults. We can re-program them.

Shane Parrish advocates for the same advice I offered in my most popular Substack article to date, Sorry Jocko, Discipline is Overrated (12K+ views). Instead of repeating what I covered in the article, I’ll summarize by saying we both posit the reason we fail to reach our goals is because relying on discipline alone will guarantee failure. Instead build systems which put you on the path to success. Re-program your defaults. If your goal is weight loss, remove sugar filled beverages from your house and replace them with healthy alternatives.

Conclusion:

Clear thinking isn’t about eliminating mistakes, it’s about stacking the odds in your favor by refusing to operate on autopilot. Parrish begins Clear Thinking by discussing barriers for a good reason. When you become aware of your defaults, you give yourself the chance to override them. That’s how better decisions are made. Not by luck, but by design. Part II will dive deeper into how to reprogram those defaults, but for now, the challenge is clear: start noticing when you’re about to act like Sonny Corleone, follow the herd, or cling to inertia. Awareness is the first step to clarity.

See here for Part II

Thank you for reading. If you liked this article please Subscribe below. I publish articles on a wide range of topics from business, books, current events or anything on my mind.

Nice summary article, Ben!

With reluctance to change you made me think of two things that I’ve seen in my work and in professional literature:

1. In change management, what seems like a small change to a change agent might seem like a huge change to someone in the target population

2. More from the world of behavioural economics. Sunk-cost bias: The cognitive bias that makes it hard to step away from something that we’ve already invested lots of resources in.

The key is awareness in these two cases, and not a lot of people stop to take the time and internalise it. Looking forward to part 2!

Thanks for sharing this. What puzzles me is why the human brain, designed for thinking, is so keen to avoid it whenever possible, despite potentially costly consequences. Unlike other organs, it gets to vote its own utility...