How To Make Better Predictions

Recapping Mauboussin's Masterpiece "The Success Equation"

George Orwell famously wrote in 1984 “Those who control the present, control the past and those who control the past control the future.” Many wish to control the future for various reasons but what if you simply want to know what will happen?

That would still be pretty great wouldn’t it?

Assuming you don’t find yourself in the same situation as Cassandra of Troy, you could steer clear of disasters, profit massively from the stock/betting markets or just have more information to make decisions with.

What if I told you over a decade ago noted investor and academic Michael Mauboussin played the role of Prometheus and shared the secrets of predicting the future.

In his 2012 book, The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing Mauboussin1 gave the best exploration in determining if outcomes were a result of luck or skill. By knowing this, we can use this to make better informed predictions or at least smarter guesses.

Today’s article will give an overview of this framework along with a few takeaways from the book.

If this week’s article does not appeal to you please check out some other recent articles

Sorry Jocko, Discipline is Overrated

How to Not Suck at Sales Part I

LLMs as Explained by The Big Lebowski

3 Suggestions to Improve the Art of Making Good Predictions:

Understand Where An Activity Falls on the Luck and Skill Axis

Is the activity you are trying to predict governed largely by luck or skill? Mauboussin defines luck as anything that cannot be controlled by the participant. If the answer is luck, you are really just playing the odds. The skill level of a person flipping a coin has no influence on the outcome otherwise there would be repeat world coin flipping champions. The less skill is involved, the harder it is for an individual to perform better than the implied odds of that activity. In a similar fashion, in an activity where zero skill is involved, somebody trying to make predictions on this activity will never be able to sustain a prediction record better than the probability rate (in the case of coin flips, 50%).

This is why if you find yourself in a situation where you are forced to bet on the International Coin Flipping Contest (ICFC), you may as well just select a name at random. On the other hand, if luck does not meaningfully influence the outcome, it is much easier to predict what will happen. Good examples of this are chess or arm wrestling; the rules and environment never change so the better player should win 99% of the time. Luck can’t meaningfully help the weaker competitor. As the predictor, if you knew which of the competitors was stronger or better at chess, your prediction would be right most of the time.

By understanding where an activity falls on the spectrum of luck-skill, you will save yourself from the pain of overconfidence in your prediction abilities.

Two common errors relate to this:

People believing that they can outperform the odds on luck driven events

Overconfidence in their ability to predict events that do involve some skill

Have you ever met anyone who claims to be great at playing slot machines? Despite their claims, there is minimal skill involved. Betting large sums of money on slots on the premise of superior skill would be foolhardy.

If you don’t have a friend like this, I’m certain you know somebody who believes they are above average stock market investors. While this does involve skill, luck is still a key factor, which can lead them to overestimate their abilities. Many investors choose to build their own portfolio of individual stocks in an attempt to outperform the broader market index (historically 8-10% per year), yet an astonishing low percentage of professional investors consistently manage to do so (more on that later).

Before making a prediction in a particular activity, figure out if this is an domain where skill plays a meaningful part, then assess if you are actually skilled at it.

2. Asses Sample Size & Significance

Part of the allure of College Basketball’s March Madness are the upsets that happen by underdog teams over large established programs. This regularly happens because the underdog only needs to win one game to advance. With good coaching or unconventional strategies the less skilled team can beat the favorite for one game. If these two teams played each other many times, the better team would win most of the games. The graph above showed that Basketball is actually a relatively low luck sport, this is why in the NBA where teams play best of 7 playoff series, the champion is always an elite team.

By increasing the sample size, the more the higher skilled participant’s edge will influence the outcome. The more that luck dominates the activity, the more you need to increase the sample size. This is why professional hockey that has the same playoff format as basketball, sees many more lower ranked teams win the Stanley Cup; there is more luck involved in hockey therefore. If NHL teams played 9 or 11 game playoff series, you would see fewer upsets.

It is for this same reason why a complete amateur can beat a professional poker player in a single hand but would be very unlikely to win if they played 10,000 hands heads-up. Even in high luck sports, as the sample size increases, skill differences become amplified. Professional Golf tournaments have 4 rounds of 18 holes to crown a winner; this is why few amateurs can win professional tournaments.

An example where the weaker party would want to increase the sample size, would be in simple activities where they have a clear skill disadvantage. To increase their probability of winning, they should modify the activity to make it more complex. A good example of this was the battle between David and Goliath; if David tried to fight in a basic hand to hand combat, he would have surely lost. He changed the rules of the game by firing stones. A common military strategy when one side has lesser numbers or military force is to employ Guerilla Warfare. Instead of fighting one large battle out in the open, they will fight many small skirmishes, often using the element of surprise.

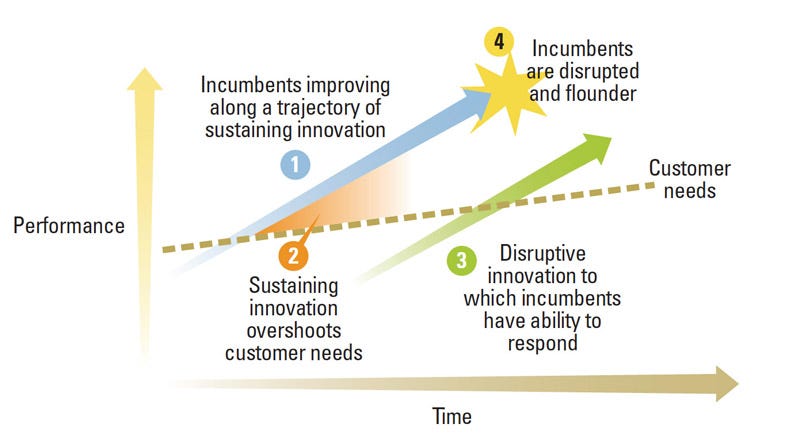

Outside of war, this can also apply to the world of business. As stated in Clayton M. Christensen’s Disruption Theory, smaller companies won’t defeat large incumbents by trying to compete directly head on. They need to start by unbundling one of their services and do it better or take a less profitable segment and then move up market.

3. Always Consider Null Hypothesis

If ever you are unsure where an activity falls on the luck - skill axis, look to see if you can find somebody that regularly beats the implied odds of that activity. If a number of participants that can regularly do this, there must be some presence of skill. To clarify, just because there is luck involved in an activity, it does not mean that the winners or participants are without skill, but rather the winner will be decided by luck.

Going back to the golf example, let’s assume that the PGA tour had only 25 players and they played 25 tournaments per year. If every season each player won only 1 tournament, the conclusion to draw would be that the skill levels are so close that the winner of each tournament would largely be decided by luck. If one player won all 25 tournaments in a given year, it would be undeniable that they would be the most skilled of the group. This is why it is fair to say that Tiger Woods was the best golfer in his era but very hard to crown the best bingo player of all time.

Outside of sports, when evaluating to what extent good investors are lucky or skilled, there would need to be enough examples of people who consistently beat the market for extended periods. There are definitely many prominent individuals such as Warren Buffet, George Soros & Peter Lynch to name a few, who have done so, indicating that their is skill involved in investing, but that does not mean you should trust your dusty friend to invest your life savings for you.

A common argument against the presence of skill in investing is that if you take enough participants in any activity, you will find outliers. Said differently, if you put a million monkeys in a room with a typewriter, one would eventually write Shakespeare. I can’t speak to the writing abilities of primates but part of the reason people can make this argument, is that an investor has a very low degree of control over the outcome compared to activities like sprinting or chess. This is why it takes a very large sample size and track record before you can definitively declare that an investor is above average. Especially in certain areas of finance such as Private Equity or Venture Capital, it can take over a decade to realize an investment.

By understanding the domain that you are trying to predict, you can avoid the common pitfalls mentioned at the beginning. Trying to outperform lucked determined events or overconfidence in skill determined outcomes. The larger the sample size, the more that the edge gained by skill influence the outcome. This is why it is much easier to predict who will finish at the top of the standings by the end of the season instead of the winner of one particular match. If ever you are unsure where you fall on the skill spectrum, judge your long term performance against the implied odds of that activity. If you are consistently performing above average, you are have skill. Appreciate that in some domains, the feedback is immediate and unambiguous such as in sprinting or arm wrestling. Others might take years or decades such as investing.

With this knowledge, I am hopeful that you can go fourth with a better framework how to isolate skill from luck, which should hopefully guide your future predictions.

That’s it for this week, I hope you enjoyed this please comment and subscribe to get access to new articles each Tuesday in your inbox!

This book was suggested by Will Quist of Slow Ventures who was a guest speaker for our On Deck Investing fellowship organized by Tom White of White Noise.