Startup Equity Explained: Basics and Considerations for Founders

Introduction to the Series & Basics to Startup Equity and Considerations for Founders

Introduction and the very basics:

Making decisions around startup equity can be daunting to even the most experienced founders & investors. Whether it is your first or 10th company, as a Founder, you face the delicate task of dividing shares in a way that makes it possible to achieve your company's goals, while retaining enough upside to benefit from a future liquidity event. Investors spend all day trying to determine which startups will be the “new new thing”, and once identified, try to determine the right price to pay to own a piece of it. Employees need to try their best to evaluate the risk reward tradeoff to joining a particular startup. This series of articles aims to give a very high level primer on many of the considerations each of these parties needs to make when trying to determine the value of their equity and when it’s worthwhile to try to get more equity or to accept dilution.

Quick disclaimer, I have never founded a company (with the exception of a single location lemonade stand in the mid nineties. Despite achieving cashflow break even within our first week, we had to shut down because of other time commitments ie primary school). My experience comes from learning and working with early stage companies for the better part of the last decade. Little of what I am sharing is revolutionary or can’t be found in thousands of other articles across the internet. This post was inspired by several conversations over the past month, with founders or people considering joining a startup but not understanding how they should be thinking about their equity.

Let’s assume you were inspired to launch your own startup and before talking to anyone, you create your company by incorporating a Limited Liability Corporation (LLC). Since nobody else is involved at this point, you assign yourself all 10 Million of the Founder Shares based on your lawyer's suggestion. At this point, you own 100% of the equity in the company. For setting up your company, your lawyer sends you an invoice, asking for $10,000 for their time and the registration costs associated with launching your business. However, they present you with an option to instead of paying them for the full invoiced amount, that if you were to trade them 2% ownership in the company, they would reduce their invoiced amount down to $1,000.

As you think about this proposition, you start working on your idea and realize that you will have a difficult time building out a prototype alone. You then bump into a former colleague, who gets equally excited about your idea and asks to join you. They understand that the company doesn’t have a product, sales or any capital yet so in lieu of a salary, they offer to work part-time on the company in exchange for 30% ownership and the title of co-founder.

While you are discussing this over lunch at a crowded restaurant, a generic looking individual in a Patagonia fleece, leans over and offers you funding for your new venture, in exchange for a number of shares that can be determined at a future date.

Later that day, you get contacted by a recruiter who tries to convince you to give up on your startup idea, and to instead join a well funded venture backed company. On top of a competitive salary, they offer you fifty thousand options in the business. In each of these cases, you must decide if what you are receiving is worth the equity you will be giving up. Here are some considerations, should you ever find yourself in any of these situations.

Professional Services/Advisors:

In the first case, your lawyers seeing that you are low on cash have given you an opportunity to save some money by paying with equity. As a founder without any external financing, this could be tempting because that is $9,000 that right now needs to come directly out of your pocket to fund. As this offer is presented, the only benefit is the immediate cost savings. To decide if this is worth considering, you would need to evaluate several factors, such as your own financial situation, the type of company you are trying to launch etc. but the main considerations any time you are considering giving up equity, is 1) How much is it worth for you today? and 2) Will giving up this equity increase your total equity value in the future? For an early stage company without any sales or even a prototype, the value of the company’s equity is completely subjective. As a founder, you can decide what that equity is worth to you, but that does not mean you will find anyone else willing to pay that price for it.

In this example, your lawyer has already placed a value on your company.1 If you were to accept their offer, it would imply that that the total equity value of your company is currently worth $450,000, you would own 98% of this company, meaning the value of your equity has an implied worth of $441,000. As it pertains to the mechanism for the transfer of shares, it can happen one of two ways: 1) You can transfer 2% worth of the outstanding share count (ex: if there were 10 Million shares created at the onset, you would send 200,000 to the lawyers, leaving you with 9,800,000 shares) or 2) You create new shares, and give them to your lawyers so that their ownership will represent 2% of the total share count (ex: Create 204,802 new shares, and transfer them to your lawyers2). Depending on which of the two methods that you use, the value of each share would have an implied worth of $0.0450 or $0.04410 ($450,000 divided by 10 million or 10.2 million). Normally, companies will opt to create and distribute new shares, but regardless of the method, even if you keep the same number of shares, your ownership will be diluted. secondary sale3.

Being able to say the company you just created, is already worth nearly half of a million dollars, does have a nice ring to it. However this does not mean you are halfway to being a millionaire. Nor does this mean this is a good offer worth taking. Simply because your Lawyer was willing to knock $9,000 off of their invoice, does not mean that somebody else would be willing to pay $450,000 to acquire all of the equity in the company. When looking at your share price, the key thing to remember is, the price you have on paper is irrelevant unless you have somebody willing to offer you that price in exchange for that equity. The fact that you just launched this company and have not even put a pitch deck together, would make it extremely unlikely that somebody would want to pay ~$0.045 a share to own 10 million shares in this legal entity.

Any time you are considering giving up equity, you must ask yourself if what you receive in exchange for this dilution, will increase your equity value when you sell in the future. Unless you are confident that the answer is yes, then you should not give your equity away. As such, the only cases where I think it would make sense to accept an offer such as this, would be if you are so cash strapped that this legal bill could make the difference between you starting the company or not. In order to do this, you must believe that something will happen soon that will convince somebody else to give you money, either in the form of funding (equity or debt) or sales, that would permit your company to afford other necessary bills and stay alive long enough.

In the case of giving up equity in exchange for Professional Services (Legal, Accounting etc.) it depends heavily on the amount of work that they will be providing you as well as their expertise, market value etc. Not many Professional Services firms will agree to work in exchange for equity, but from the cases I have heard, this could range anywhere from 0.25% - 1% of total equity ownership, depending heavily on the state of the firm when the engagement begins. For Bootstrapped companies, this might make more sense if you receive large bills and can’t tap into other sources of funding.

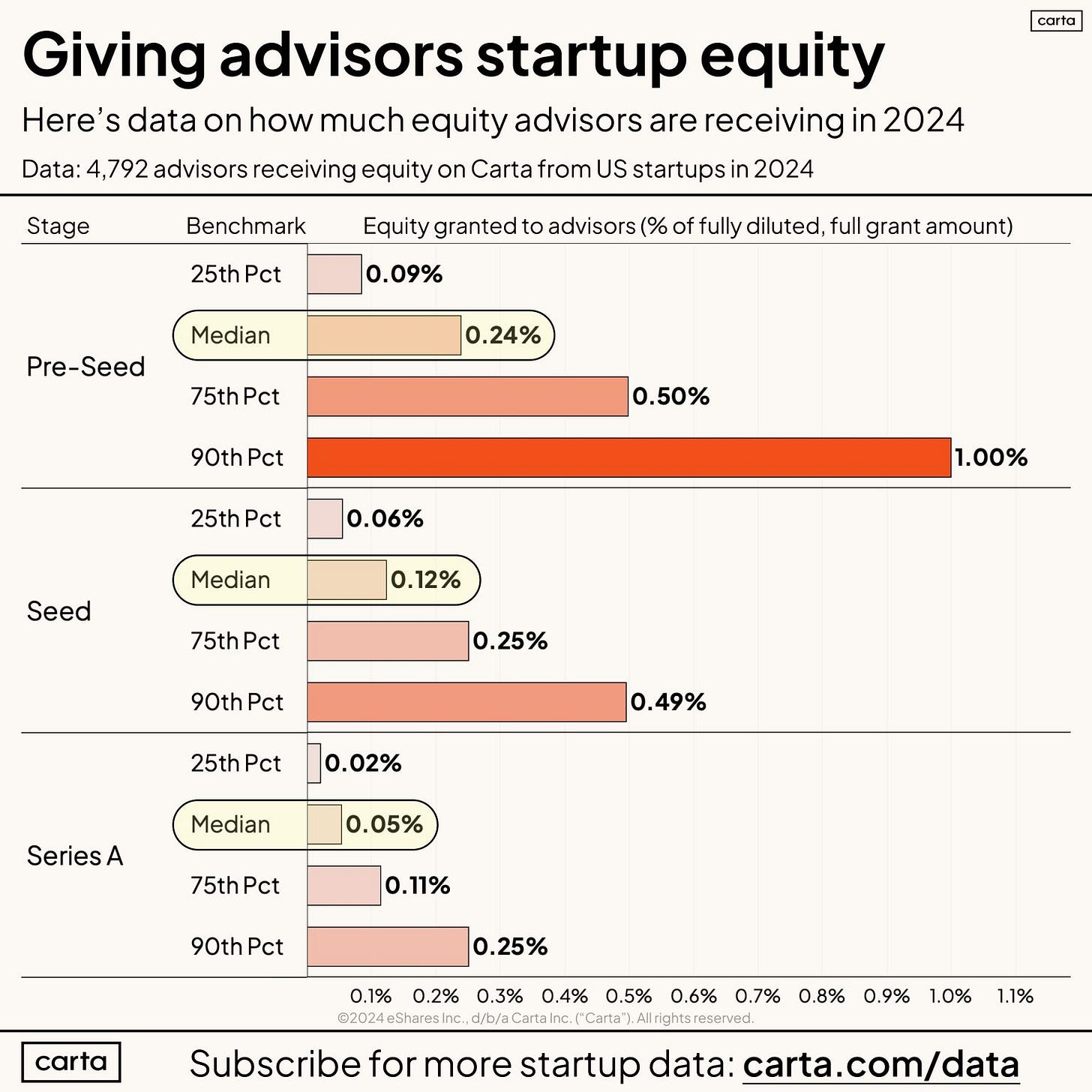

Advisors can be considered similar to a Professional Services firm/consultant, in that they are offering you their time, expertise and access to their networks in exchange for a small ownership in your company. Advisors can get involved at any stage of the company. Some might be very involved, willing to meet with the founder weekly, others might have limited involvement. To ensure that Advisors actually provide some sort of value in exchange for the equity, it is common for their agreements to have necessary milestones they must hit in order to earn the equity. Typical allocations for advisors in venture backed companies can range anywhere from 0.02% up to 1% (SVB).

When faced with ownership dilution questions, if you are starting this company with the primary objective of personal enrichment, you will weigh whether what you are getting in exchange for the equity today, will lead to a higher equity value in the future. If your objectives are more mission oriented, or you are not motivated by wealth, you might prioritize control instead. Each shareholder will have different objectives, however for the purpose of this text, we will assume that maximizing equity value is at least one of the primary objectives of the Founder or other Shareholder.

In general, you should try to avoid giving away equity during the earliest days of your company, as this is when it’s least valuable. If you give away too much, too soon, it will create headaches for you down the line (see Investor section in Part Two). Unless you really cannot afford the bills at the beginning, you are better off paying with cash instead of equity. Most Professional Service firms, willing to deal with startups will be understanding if you cannot pay immediately but you will need to come up with a way to pay them within a few months or up to maximum one year. Advisors can be worth the equity if they make contributions that help meaningfully increase the value of the company. They can do this through helpful advice (they are advisors after all), setting up key processes (Sales, Finance, Tech Infrastructure etc.), leveraging their networks to help land investors or early key hires. Ideally this support is on-going, even after their vesting period ends, which they are incentivized to do, because the better the company does, the more their equity will be worth.

Co-Founders & Early Employees:

In the second example, a former colleague of yours has offered to join your company on a part-time basis, as a co-founder in exchange for 30% of the company’s equity. You have accepted that it will be difficult for you to build a prototype of your product alone. With your former colleagues' help, the likelihood of being able to deliver this prototype goes up dramatically. It is not uncommon for a company to be launched by a single founder, who later adds co-founders.

In this example, the company was just incorporated and not much has been built. You acknowledge that your former colleague will be a big help in getting your prototype built, which will be needed to win over prospective customers or investors. However, 30% is a massive portion of the company, and you need to think long-term when making decisions related to equity allocation.

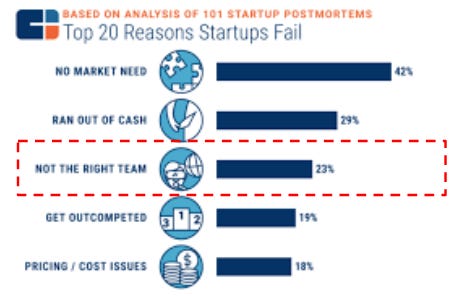

At this amount of equity, your former colleague will own a sizable amount of the company, for the foreseeable future. What if after the prototype is built, you realize that they lack the skills needed to lead an engineering department? Perhaps your former colleague never feels quite ready to leave the security of his current job and wants to remain part-time much longer than what was originally discussed. Building a business is a long term commitment and success is difficult, even with a great founding team. You cannot guarantee success, with the perfect founding team, but you can guarantee failure with the wrong group. One of the most common reasons startups fail is because of founder breakup. Different investors report anywhere from 10-35% of companies they have invested in have had a Founder leave .

If early on, one of the co-founders or employees leaves while holding a meaningful amount of equity, it would create a situation where a shareholder that did not invest capital or is actively working on the company, is one of the largest beneficiaries in the event of a future exit. This is not something that active employees, current or future investors will appreciate. Such a situation is known as “dead equity”. To reduce the possibility of this happening, co-founders and employees earn their equity on a vesting schedule. The standard vesting schedule is 4 years with a one year cliff.

The cliff is the cut-off date that you need to surpass if you want to earn any equity, at all. Assuming the grantee makes it past one year, they earn an increasing percentage of their equity, until the end of their 4 years (48 months). Once the vesting period is finished, they will have a predetermined period when they can exercise these options (this could be anywhere from months to years). If a founder or employee makes it to the end of their vesting period, they will be entitled to the amount of stock options allocated to them. Once these options are exercised and converted into common shares, even if the founder/employee leaves the company, they will own them until they sell or the company shuts down. The vesting period at least provides some protection and a guarantee that the employee/founder will need to be there for at least the length of the vesting period. Additional measures or incentives can be added in the form of milestones, if sides cannot align on a predetermined number of options.

Going back to our example, the offer made by your former colleague could be worthwhile if you believe they are the right person to help achieve your vision for the company (short and long term). By having the agreement vest over multiple years, it can help de-risk things, and mitigate the dead equity problem if shortly after they join, you realize they are not the right fit. You can further strengthen the protections, by requiring that they deliver a functional prototype before the end of the option cliff. When negotiating equity allotment, you want to ensure that you are not giving too much away but at the same time, if this is the right person, you want to ensure that they have enough ownership that they will feel incentivized to want make the company successful and stick around at least through their vesting period.

When trying to decide how much equity to offer a co-founder or key hire, you should consider a few factors such as:

How much do you believe this person will increase the total value of the company? If they are capable of building the most innovative and differentiated product for your segment and getting many other talented people to join the team at below market salaries, it makes sense to give more equity to them compared to somebody who is only average at their position.

What is this person’s opportunity cost for joining (how much would they be getting paid elsewhere)? If the opportunity cost for them joining is very high, you will likely need to offer them much more equity, unless you are at a stage where you can afford to pay high salaries.

How invested in the mission are they? Promises of future equity value will only get you so far. If somebody is only joining on the basis that their stock options will one day be worth a lot of money, they will be a major flight risk the minute they feel things at the company are not going so well, or if they see an opportunity to make more money elsewhere.

How much do you trust them? Just as important, is this somebody you believe you can work well with, to accomplish great things? Launching a company with somebody you met at a networking cocktail event, after one conversation, could work out but I also wouldn’t be surprised if the company would be shut down a few weeks later or the first serious argument (whichever comes first).

What stage is the business in? Just like for employees, the earlier somebody joins, the more risk they are taking. If you are trying to convince somebody to join your company that is pre-product, pre-revenue and has not raised any external capital yet, the company could cease to exist in a few months. The probability of being able to exit at a high equity value is so low, small amounts of equity are practically worthless at this point. As the company increasingly shows evidence of product market fit (there is a clear need for the product/service you are selling and people are willing to pay for it), the less risky joining becomes. It is for this reason, it makes sense to offer employee #5, more equity than employee #50, even if they have the same title & responsibilities.

When it comes to co-founders or executives, they likely have many opportunities available to them. If you are confident that this is the right person to deliver what you need from them, it might make sense to give them large swathes of equity, even if you have already proven product market fit and raised millions of dollars. If you could get Mark Zuckerberg to leave META to join your startup, you will likely need to offer them more than a couple percentage points. This is why there is no exact formula for determining what is the right amount of equity to grant to a co-founder or employee, and it will be different for each person. However, the earlier the person is joining, the more valuable this person will be to the company, and the harder it would be to find a replacement for this person, the more equity this person should command.

(Table was made by Kevin Vela 2017)

Keep in mind though, that companies generally last much longer than their original vesting period, co-founders and employees can get multiple stock option grants during their tenure with the company. While the strike price on these options will increase over time, you can always issue more options to founders and early employees. This will also help offset dilution that will occur as outside investors contribute capital to the business.

(In the follow up articles we will discuss startup equity from the perspective of investors and employees)

If your lawyers are willing to forgo $9,000 in exchange for 2%, this would imply they currently value the entire business at $450,000 ($9,000 divided by 2%).

If 10 Million is the current number of shares before the transaction, and 10 million will be worth 98% (100%-2%) after the transaction, by dividing 10 million by 98%, you will get the total share count after the transaction 10,204,802. In this case, all of these shares are going directly to the lawyer, they would own 204,802 shares or 2% of the total share count, your original 10 million would now represent 98%.

When new shares are created and distributed, this is known as a primary sale (the second method). When an existing shareholder sells their shares to a new or different existing shareholder, this is known as a secondary sale (the first method).