Is Alex Karp a Kafka or Dostoevsky Character?

If we are stuck in a Kafkaesque nightmare, is Karp the protagonist or villain?

I always have a couple books at my disposal. A strange set of circumstances resulted in me reading The Trial by Franz Kafka and The Technological Republic by Palantir PLTR 0.00%↑ CEO, Alex Karp, at the same time. At a glance, you would expect the two books have nothing in common. They were written 100 years apart, one is a work of fiction by one of the great writers of the 20th century; the other is a nonfiction book by a technology CEO.

Upon reflection, I saw a strange parallel. The Trial depicts a society where individual liberties have been replaced with an ever-growing bureaucracy, designed to further perpetuate itself, at the expense of everyone else. The Technological Republic, on the other hand, argues that this is what our society will become if we do not stand up for individual liberties, which are among the hallmarks of Western civilization. The way we defend these liberties, is technological and military superiority.

Translation: He wants you to buy more Palantir stock. If you are a short seller, he especially wants you to put down the coc@a!ne and reverse your position. Karp is a colorful character. Since Palantir has become a stock market darling, he has become increasingly outspoken. One of the topics he has regularly discussed in public is his belief that Silicon Valley companies should focus more on solving problems related to national security instead of launching another photo-sharing app.

(not AI, he did this during a live interview)

This article will give a short primer on The Trial and what Kafkaesque means. Discuss what Alex Karp wrote about in The Technological Republic, and contemplate whether his views and actions would be consistent with a Kafka protagonist or other great characters of literature. If you haven’t already clicked off, buckle up, buckaroo!

But first, make sure to hit the Subscribe button below to join the nearly 1,000 Subscribers that get articles like these, delivered directly to their inbox.

If this week’s article does not interest you, please check out some other recent ones:

The Trial & A short intro to Kafka

Franz Kafka’s The Trial is one of the most unsettling novels you’ll ever read. Josef K., is arrested and prosecuted without ever being told what crime he committed. He becomes the latest victim of a nightmarish legal system, where guilt is assumed and justice is just an abstract concept without a functional reality. While it’s a darkly funny, it lingers with you as the weight of the implications settles in mostly because of how prophetic it turned out to be.

The Trial was published in 1925, shortly before the rise of the National Socialist (Nazi) party in Germany. Soon, Kafka’s absurd bureaucracy would be mirrored in real-world horrors, where Jews, like Kafka would be arrested without accusation, due process, or access to a legitimate court. The legal machinery that devoured Josef K. in fiction became horrifyingly real, ultimately culminating in the Holocaust, where millions of Jews and other targeted groups were systematically exterminated. Kafka, who died in 1924 from tuberculosis, would not live to see these events unfold or he likely would have perished in a concentration camp, like most of his family.

The Trial is not about hateful political ideologies but rather the crushing weight of excessive bureaucracy. A system that no longer serves people but instead perpetuates itself for its own sake. I wrote about this earlier this year in How Society Uses Bureaucracy to Keep You Safe but Miserable, before I started The Trial. I took a different approach but the bottom line’s the same: if bureaucracy is not actively kept in check, it will become overgrown and eventually erode everyone’s freedom.

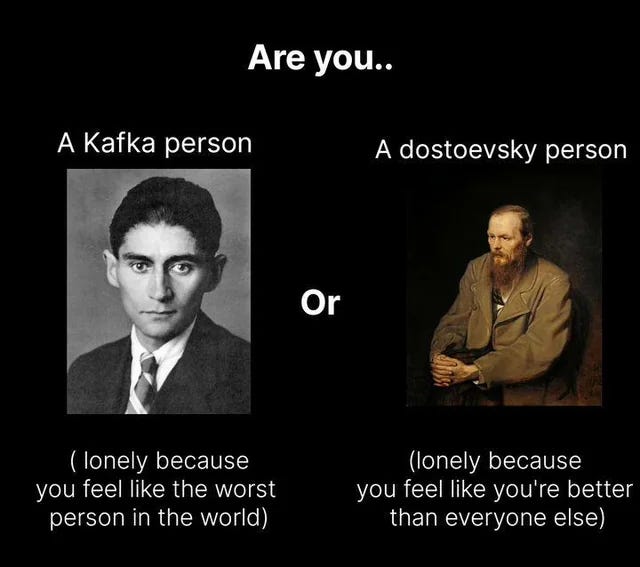

Beyond bureaucracy, Kafka’s novels discuss themes such as dehumanization, authority and existential isolation. His work is so iconic, that people refer to things as Kafkaesque when a situation is surreal, oppressive, and/or absurd. The term is often used to describe when individuals are caught in nightmarish bureaucratic loops, against nameless/faceless illogical agents acting on behalf of an uncaring system. In Kafka’s novels, the protagonists are generally the victims of these bureaucracy, yet still choose to fight or reason against their oppressors. These characters often exhibit alienation, guilt, and deep self-doubt, making them appear depressed or overly self-critical, as though they are fundamentally flawed.

If you contrast this with another great fiction writer of the 20th century, Fyodor Dostoevsky, his characters often go through major moral and psychological turmoil, and encounter existential questions. They differ from Kafka protagonists in that they often perceive themselves as more enlightened, morally superior, or "better" than the people around them. Therefore depending on how people perceive themselves, we can decide if they are a Dostoevsky or Kafka character.

We can all find ourselves in Kafkaesque scenarios; anyone that has ever gone to renew their drivers license or apply for a permit, will attest to this. Yet when faced with this scenario, do you accept your fate or try to be like Josef K? Alex Karp sees the West approaching this.

Alex Karp & Palantir

Before co-founding Palantir 20 years ago, Alex Karp did not fit the bill of the typical Silicon Valley Founder at the time. Instead of coding late into the night on side projects, he was busy earning his law degree from Stanford and a PhD from Goethe University. Karp started his career at the Sigmund Freud Institute, an institute focused on psychoanalysis, as per its namesake. He ran a hedge fund for a couple of years before joining Palantir with his former Stanford classmate, Peter Thiel in 2004.

Palantir Technologies is a software company that specializes in data analytics. They work with many large companies but they are primarily known for partnering with governments and military organizations. They first rose to prominence when reports suggested their work aided the operation that led to the death of Osama bin Laden. Shortly after, documents leaked by Edward Snowden indicated that Palantir played a role in supporting the National Security Agency's (NSA) surveillance programs, which were designed to monitor and analyze global internet traffic. Despite questions about these programs, nothing hindered Palantir’s growth.

In 2024, Palantir generated ~$3B of revenue, while growing at a rate of around 30%; they currently have a market cap of around $200B, which is in line with Salesforce CRM 0.00%↑ and Adobe ADBE 0.00%↑ that generate around 10 times more revenue. The market is currently rewarding Palantir with a very high multiple, which means investors expect sustained future growth.

This can be partially explained by the many ongoing military conflicts providing a boon for military and defense stocks. The United States alone spends nearly a Trillion dollars per year on military and defense, meaning there is plenty of money up for grabs for those that can secure those sweet government contracts. Possibly inspired by the success of Palantir, there has been an emergence of newer startups entering the space. VCs are suddenly very interested in funding defense-tech companies, investing $3B in 20241. This contrasts sharply with when Palantir started; Karp said no VCs were interested in the sector, forcing them to raise funds from the CIA and Thiel’s Founders Fund. This is why, two decades later Karp can confidently take a victory lap, since those investments paid off handsomely and Palantir is well positioned as a leader in a space that is suddenly the hot thing.

The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West

Alex Karp through The Technological Republic posits the West's technological leadership is endangered by a culture of complacency and misaligned priorities. He believes Silicon Valley has deviated from its historical collaboration with the government on significant technological advancements, such as the internet. Instead founders have been focusing on photo sharing apps and other trivial products. This is consistent with Thiel’s famous quote:

"We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters."

Karp sees this shift as part of a broader societal trend where intellectual fragility and a lack of ambition have infected academia, politics, and business, making this generation weak and less equipped to address, real pressing challenges. He’s certainly not the only person to lodge similar complaints about Silicon Valley innovations failing to address more important issues. For Karp, ensuring Western Democracies, remain the most technologically advanced is the most critical issue of the day. This is needed to maintain hard power, and soft belief.

If the US does not win the emerging artificial intelligence race, it will cede its superiority to rivals such as China, which has a different set of values. This might sound obvious, but as Karp sees it, many people in Silicon Valley and major institutions, are unwilling to say the quiet part out loud, America/the West needs to win. They are afraid of alienating anyone, so they choose not to say or stand for anything.

When Karp sees employees at big tech firms such as Google and Microsoft unwilling to work with the US military, but having no qualms working with the Communist Party of China (CCP), he sees this as an example of people wishing to benefit from the comforts of Western civilization without doing anything to protect it. Karp does not believe you can fence sit. You either support a cause, or you support its opposition. If you don’t support America and its allies, then you are for their enemies. Most people try to pretend these dilemmas do not exist, but in a competitive situation, opting out, is tacit support for somebody. This is effectively the trolley problem.

Many in positions of power feel unable to express their perspectives on issues of consequence, without potentially damaging their institution. However, not offering an opinion, is sometimes worse than taking a position. Karp highlights how this led to the ousting of former Ivy League Presidents Claudine Gay and Liz Magill; when they failed to denounce on-campus antisemitism. Karp doubts they are antisemitic or supported what they saw, but chose not to do anything because they felt unable to exercise their personal judgement, without in some way alienating a stakeholder of their university. In essence, they found themselves on the trolley and instead of choosing a track, they stepped out of the control room, hoping they would not be held responsible for the outcome. This approach failed them.

Karp on the other hand is not afraid. He has risked alienating customers and employees by taking public stances supporting Israel after the attacks of October 7th. He and Palantir were among the first Western companies to visit Ukraine after the invasion by Russia. Karp sees the situation as absurd. The West is in a great competition, yet many of its brightest technologists don’t want to help them win, which aids the competition. As CEO, Karp does not believe his job is to be a soulless agent serving only the system and shareholders. Therefore this begs the question, is Karp a Kafka or Dostoevsky character?

Conclusion: Who is Alex Karp?

Undoubtedly, Karp in his public appearances is giving off Dostoevsky main character energy. He does not follow the generic strait laced, publicly traded tech company CEO playbook. He’s brash, loud and unapologetically outspoken when sharing his views. On the spectrum he’s much closer to believing he’s the smartest person alive instead of being fundamentally flawed. While right now Palantir’s share price is on an incredible run, and he’s flying high, markets can be unpredictable and this can change almost overnight, just look at Zoom ZM 0.00%↑ shares over the past 5 years.

Yet, you cannot overlook some absurd contradictions in Alex Karp’s rhetoric. He criticizes Silicon Valley for prioritizing trivial consumer apps over serious technological innovation, yet his co-founder, Peter Thiel, helped bankroll the very social media revolution that led to that shift. He argues that American tech companies have a moral duty to strengthen the West’s technological superiority, yet Palantir’s involvement in NSA surveillance raises questions about whether all "Western values" are being upheld equally. If Palantir and other American big tech companies win, how certain are we, we can still enjoy all of these freedoms2?

This paradox makes it difficult to place him cleanly in the Dostoevsky or Kafka archetype. If the West maintains its technological dominance, Karp will be seen as a visionary that saw what others didn’t and prevented the decay. If the West loses the AI arms race and America cedes control to adversaries, then Karp was a Kafka protagonist, that saw this happening but lost because too many in our society were afraid to standup for something. Perhaps it doesn’t matter whether we win this technological war or not, because one way or another, we will all be Josef K.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article. Please Subscribe or Share Some Feedback in the Comments

Half of this came from Anduril who raised $1.5B

His condemnation of short sellers is also ironic because he and Thiel both ran hedge funds that likely engaged in similar tactics against others. Perhaps the difference is it wasn’t done to pay for recreational drug use.

Karp "criticizes Silicon Valley for prioritizing trivial consumer apps over serious technological innovation, yet his co-founder, Peter Thiel, helped bankroll the very social media revolution that led to that shift."

Weird to think that Facebook enabled Palantir, in that Thiel's returns from his early investment in Facebook allowed him is what allowed him to invest heavily in Palantir.

The deepest irony of Karp is that his beloved venture ecosystem will be what creates the dystopia he envisions. POSIWID at its finest-if venture capitalists saw future tech and geopolitics as worthwhile investments, they'd throw money at it like everything else. Instead, we have software.

I remember seeing the Andreesen Horowitz crypto slides back in 2021. I wonder if they're still selling that product as the future of Earth or whether a certain trend has supplanted their portfolio.