Is Skiing a Dying Sport? A Look at Its Past, Present, and Future

The unofficial history of skiing, will the Epic Pass kill the sport?

Skiing is sick.

It’s a super fun activity, that appeals to adrenaline junkies and raclette aficionados alike. On the other hand, rising costs coupled with shorter ski seasons, are putting its future in question.

Skiing went from a means of survival, to a leisure sport enjoyed by millions. Despite ebbs and flow, adoption and participation has steadily risen over time. Although the 2022-2023 season posted among the highest participation ever in the US, there is reason to suspect the sport will eventually start to level off then decline.

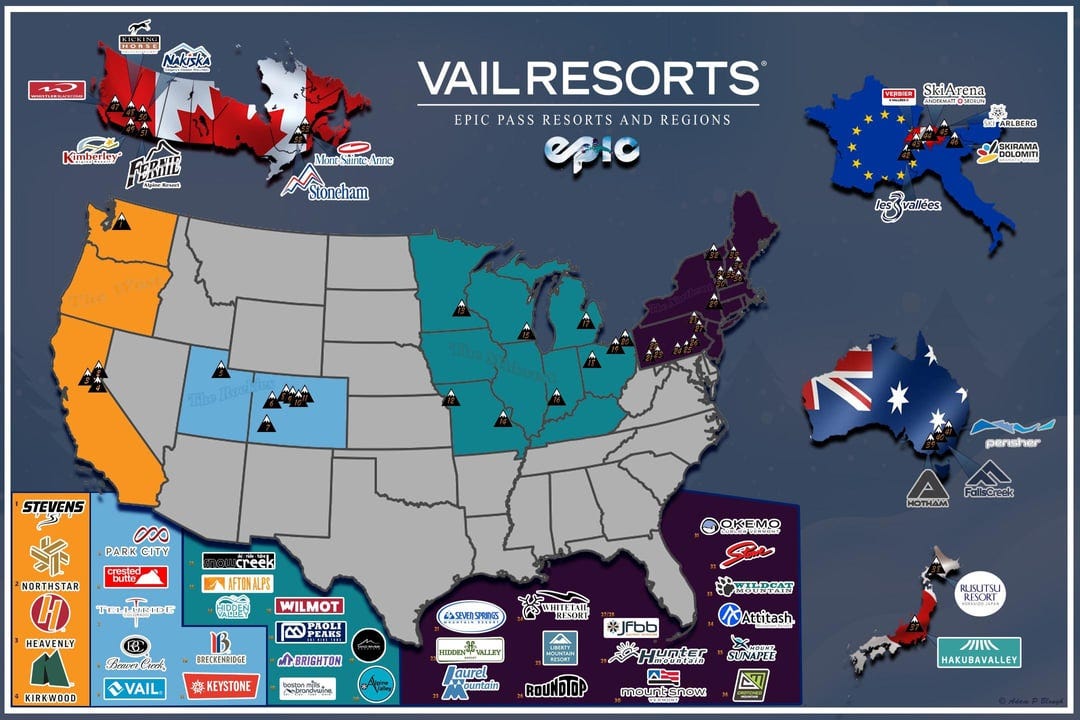

Recreational ski resorts are a $4.2 billion dollar industry, with Vail Resorts being the largest player in North America. Vail offers Epic passes, which gives unlimited access to more than 40 mountains worldwide. This change made their business model more predictable and less exposed to variant weather. While it’s good for avid skiers, it has helped contribute to making the sport increasingly inaccessible for all but the wealthy.

With rising costs, shorter seasons and fewer people able to participate, will skiing still be a thing a few generations from now? Let’s inspect.

If this week’s article does not interest you, please check out some other recent ones:

Short History of Skiing

How it Started: Skiing as Survival

Beginnings (~6000 BCE):

Long before après-ski and overpriced lift tickets, skiing was purely about survival. In snowy regions like Scandinavia and Siberia, people needed a way to hunt and travel. They found skis in Russia, going back thousands of years. These early skis were made out of wood with animal fur covers and leather bindings. You can find the same pair if you dig deep into your parents garage, behind all the exercise equipment you bought for your home gym. Don’t worry, I’m sure you’ll use it eventually.

Estimates suggest early skiers could cover up to 50 km (31 miles) a day on these bad boys; a feat modern Nordic athletes probably couldn’t do. These days you’ll be lucky to convince someone to walk 5 km without hearing them whine about optimal ankle support or the need for custom insoles.

The Birth of Fun: Downhill & Leisure Skiing

19th-20th Century: Norway, Switzerland, Ski Clubs, The Olympics and Technology Enter the Chat

Alpine skiing began as a sport for the fanatics and the rich. The first known recreational use is widely credited to Telemark, Norway, where pioneers like Sondre Norheim developed heel bindings, making controlled downhill skiing possible. (Though, let’s be honest—other regions probably claim to have invented it, too.) With the ability to control speed, skiing quickly shifted from a means of survival to something done purely for the thrill of going fast.

By the late 19th century, British aristocrats began flocking to the Swiss Alps during the winter, transforming skiing into a fashionable pastime rather than just a practical skill. The rise of mountain railways made previously remote alpine villages more accessible, fueling the sport’s rapid expansion. This surge in popularity led to the emergence of the first organized ski clubs in Scandinavia and Central Europe, formalizing the activity into a structured sport.

While skiing competitions had been held for decades, alpine skiing wasn’t recognized as an Olympic sport until 1936, when the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Winter Games in Germany introduced it for the first time. Early enthusiasts were mostly ski club members who trained to compete. However, the sport truly exploded in popularity with the introduction of ski lifts and gondolas in the 1940s and 1950s—suddenly, skiing wasn’t just for die-hard racers; it became an accessible, mass-market leisure activity. Technological advancements in ski equipment also made the sport safer and more beginner-friendly, further widening its appeal.

This ushered in a boom in ski resort development across Europe and North America. Former mining towns like Aspen successfully reinvented themselves as ski destinations. Meanwhile, places like Vail were purpose-built from the ground up to emulate the charm of Swiss alpine villages. The industry experienced steady growth throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, peaking in the late 1980s as the number of ski resorts reached an all-time high.

Rising Cost of Skiing: 1990s versus Now

Higher Costs, Consolidation and Pricing Scheme

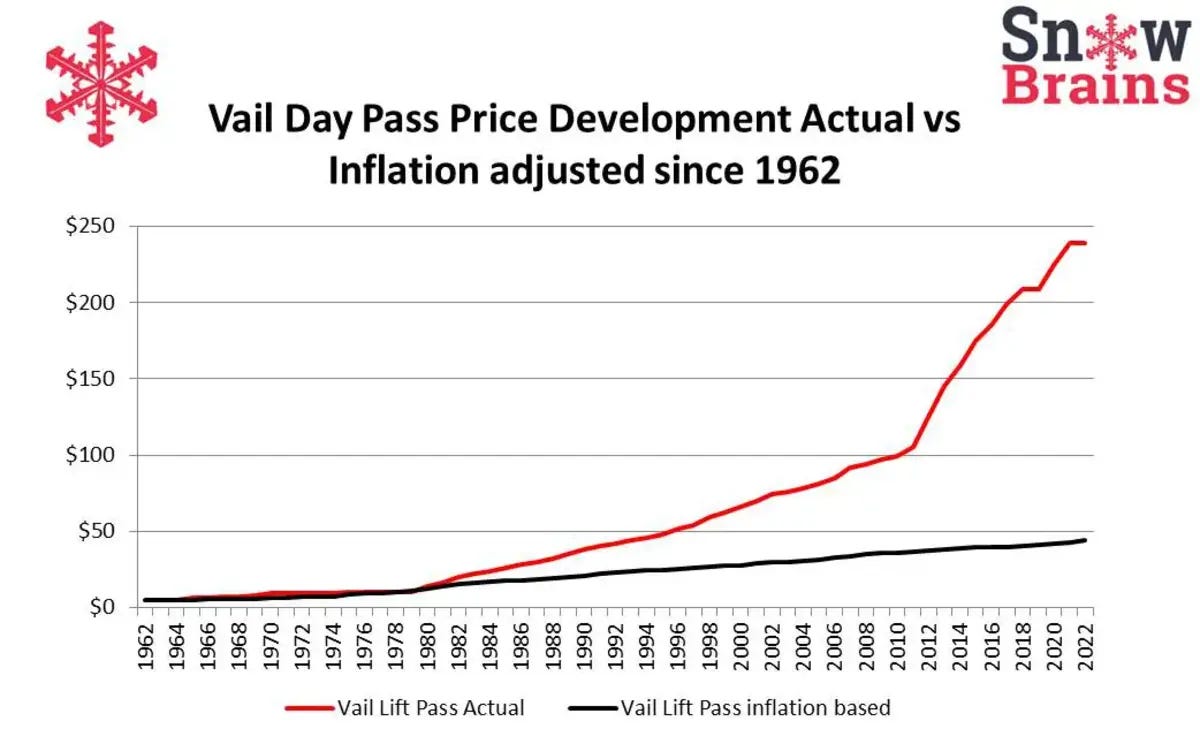

If you feel like skiing has gotten absurdly expensive, you're not imagining it. The cost of a single-day lift ticket has risen well beyond inflation. In the early 1990s, skiing at major resorts in the Northeast cost around $35–$40 per day. Today, for those same mountains, you're looking at $150–$200 or more. Adjusting for inflation, prices should be closer to $75, meaning some lift tickets are 3x more expensive relative to inflation.

There are a few drivers behind this staggering increase. Part of the story is infrastructure investment—faster, higher-capacity lifts and advanced snowmaking systems, among other required capital expenditures. The bigger culprit is industry consolidation and the shift toward season passes (more on that in a moment).

For casual skiers, the math is brutal. Paying $200+ per ticket is steep enough, but if you're a family of four, a single day on the slopes can easily exceed $1,000—before rentals, food, or lodging. These price points make skiing inaccessible for most people. Although I suppose the advantage a family has over single skiers, is they don’t need to pay for four pints of Häagen-Dazs and endless alcohol to forget how alone they are.

Vail, Alterra, and the Shift to Subscription-Based Skiing

Operating a ski resort is not a hobby, it’s a full time business with two companies dominating the North American market: Vail Resorts and Alterra Mountain Company. Between them, they own nearly 50 ski destinations worldwide. Vail Resorts offers the Epic Pass, an unlimited-use pass across its portfolio for around $1,000. Alterra Mountain Company has the Ikon Pass, which follows the same model1. With single-day lift tickets exceeding $200, these passes are a great deal for avid skiers, breaking even after 5–6 days of skiing.

The reason Vail and Alterra chose to consolidate ski resorts is simple: risk diversification. By owning mountains in different regions, Vail and Alterra hedge against unpredictable weather, which is increasingly critical as climate volatility continues to shorten ski seasons2. They also get the conventional benefits associated with scale and owner higher market share, one of which is pricing power.

Instead of offering below market prices to hurt competition, they trick customers into paying more with a traditional marketing method of the unlimited volume discount. Many industries do this but for the sake of skiing and snowboarding, Vail and Alterra:

Raise single-day ticket prices so they seem ridiculously expensive

Offer an unlimited-use pass at a price comparatively low enough that it makes skiing multiple times feel like a deal

Encourage customers to prepay thus guaranteeing revenue, regardless of how much they actually ski.

For those who ski every weekend, these passes make total sense. Someone skiing 10–20 days a season sees their per-day cost drop to around $50–$100, closer to the inflation-adjusted prices of the 1990s. But for the casual skier, going just 1–4 times a season, this absolutely sucks. You are forced to choose between paying sky-high daily ticket prices (~3x more than past generations), or dropping $1,000+ upfront, unsure if you'll ski enough to justify it.

For budget-conscious people, skiing is a tough sell unless it’s their primary winter activity. So this change has effectively made it such that participation is shifting back to its original base: the hardcore and the rich (before yelling at me see the footnote).

Earlier in the year, Vail Resorts announced plans to streamline efficiency and optimize operations…yada, yada, yada. Their stock price is hovering 50% of its 2021 peak, and revenue is flattening. Clearly they’ve reached the point that they can’t keep raising prices so they need to lower costs to achieve profit targets; a bearish sign. For good reasons, since I don’t expect these are short term headwinds.

The Geography Problem: Skiing’s Shrinking Future

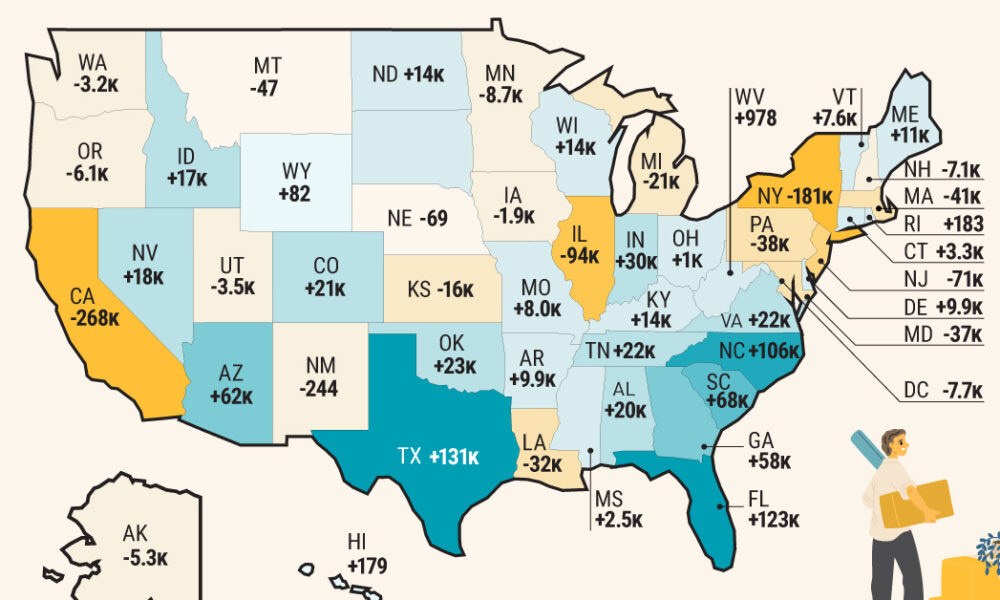

Beyond the sky-high prices, geography itself is a natural barrier to skiing’s growth. Participation rates in non-winter countries are normally single-digit percentage points, and shifting U.S. demographic trends aren’t doing the sport any favors. States with large net migration growth, Texas and Florida, have little to no ski infrastructure. Meanwhile, states with heavy skiing legacies like California and New York are facing a net exodus. If these trends continue, the number of people who live within driving distance of a ski resort will shrink, limiting the potential skier base even further.

This will create a vicious loop, because if fewer people ski, prices will need to increase or additional independent hills will go under, creating more concentration. This will make skiing even more expensive, further limiting the number of participants who can afford it. Repeating the cycle. I think you see where I am going with this.

Despite a recent uptick in skier visits, skiing as a mainstream sport is likely near its peak. The average age of ski participants is increasing, with youths (17 and under) representing a smaller percentage of ski population at a staggering rate3. At this rate, within a few decades, knowing someone who skis might feel as rare as knowing someone who plays polo. A niche activity for the wealthy and the obsessed. If you’re a hardcore skier, you’ll probably find a way to keep the tradition alive, dragging your kids onto the slopes whether they like it or not. But if you’re not? Let’s be real, your children are more likely to stay glued to their iPads than take up a sport that requires thousands of dollars, a cross-country flight or stepping outside.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article. Please Subscribe or Share Some Feedback in the Comments

Major simplification for both. There are different types of passes, ranging in prices. This does allow people to buy passes for less than the $1,000 unlimited option, but these passes carry restrictions or only work well for people living near certain locations.

Varies by region but we’ve lost about 1 week of winter over the past 20 years. A seasonal business like skiing losing a week, could represent a 10% drop in sales. Incredibly painful.

Youths made up 27% of visits nationally in 2023-2024, while still the largest age group, this is down from 31% a decade prior as per National Ski Areas Association.

Private equity ruins everything

The classic: it’s so crowded, nobody goes there anymore.